What makes someone an artist?

I often think about the role of the artist, its relevance, and what it contributes to the world. The figure of the artist has been redefined many times throughout the centuries, mostly in relation to social and economical changes: artisan, court painter, “genius” supported by patronage, in-house creative, freelance artist, content creator… But in essence, art is self-expression and that goes beyond job titles. And at the same time, it is complicated to identify as an artist without making a living out of it in a world where it seems like your value and identity are tied to a job and an income.

As an artist with a part-time job, on one hand, I frequently feel like my job in retail is one that is undervalued and alienating (you feel easily replaceable) and, at the same time, my role in the arts can also be seen as useless or superficial in the grand scheme of things. In the face of crisis, if we follow the narrative of the survival of the fittest and navigate the world in terms of usefulness and profitability, it is easy to ditch people and the arts. There is this paradox where the consumption of art products is highly encouraged, but the people who create said art are looked over.

Art is fluid and beyond metrics

In an individualistic and reductionist framework, labels are encouraged (as categories make things simpler); forcing us artists to package our skills to make them marketable through products and services. This need to make our practice sellable also pushes us to a state of mind of scarcity (not-being-good-enough and not-doing-enough) — the most palpable example being the impostor syndrome. “Well, calling myself an artist is a bit pretentious and I’m not even that good at it”, or “I don’t create frequently enough”, or “I still haven’t found my style”, or “I don’t make a living out of it so I can’t say this is my job”. I find impostor syndrome to be similar to what Byung-Chul Han deems as the “performance-oriented subject”, a result of the world we live in:

“Self-exploitation is limitless! We voluntarily exploit ourselves until we break down. If I fail, I take responsibility for this failure. If I suffer, if I go bust, I have only myself to blame. Because it is wholly voluntary, self-exploitation is exploitation without domination. And because it takes place under the guise of freedom, it is highly efficient.” [1]

In this race for commercial appeal, we inevitably enter the realm of (personal) branding, even though we, as people, are not products nor consumables… Anybody who has embarked on an artistic journey has found themselves pondering how to “have a unique style” or how to “be original”; in other words (in advertising lingo), how to “find your niche”. I would say that the weight of labels has become more acute in the internet era, with the practical languages of SEO and hashtags engrained in our everyday actions.

Ultimately, we are putting our vast creative energy into boxes, labeling them so they are easy to understand and consume. Capitalism encourages the search for originality and difference, as long as it is marketable, profitable, and does not get in the way. Uniqueness is attention-grabbing. We see this all the time with greenwashing, pinkwashing, and other “socially conscious” marketing techniques.

Inevitably, artists end up conforming to this search for identity, molding their creativity to fit into these very restricted spaces and reducing the vast realm of possibilities of our creativity into digestible bits that can be produced over and over again. Having a style demands making art as a commodity, with all the connotations attached to it: consistency, predictability, celerity, measurability.

Art is relational, made by and for the collective

Back to my initial definition of what makes someone an artist… if art is a way for self-expression, which is getting to know ourselves and the world around us —a way of navigating life— it is, by nature, shapeless and ambiguous (not restricted), active (not a passive product), in the realm of possibilities (not in the realm of certainties), unexpected and broad (not consistent). Having a style does not matter because art is the pure expression of our voice and all the things that are tangled in it. There is no rush in finding a style when it is a process-based practice. Of course, by saying that art is shapeless, I do not intend to deny it is affected by the conditions and limitations in which it is created, but instead, that creating art from a reductionist “cookie-cutter” perspective is alienating.

Reading this interview with Sophie Strand, I thought about how important is to understand ourselves in a wider context, beyond the boundaries of our individuality:

“A bunch of anthropologists went into these high oral residue communities, I think somewhere in Russia… where oral culture was still dominant. And they would ask these questions. They would [ask] how do you define yourself? Who are you? And in oral cultures, where people hadn’t had a lot of exposure to writing, they never gave information about themselves when asked that question. They would always say, I do this, these are my people, this is how I am useful to the fields around me. I have carried on the stories of my great grandfather… They would never give information about an individual self. It was always relational.” [2]

Our art is always relational, always influenced, always a heritage, always circumstantial — because we as human beings are! Once again, art is just an expression of our nature. In all honesty, I do not think that my work is original per se, as most of my themes come from different traditions and symbols, just a reflection of life as I see it. They are all branches of the same tree, affluents of the same river.

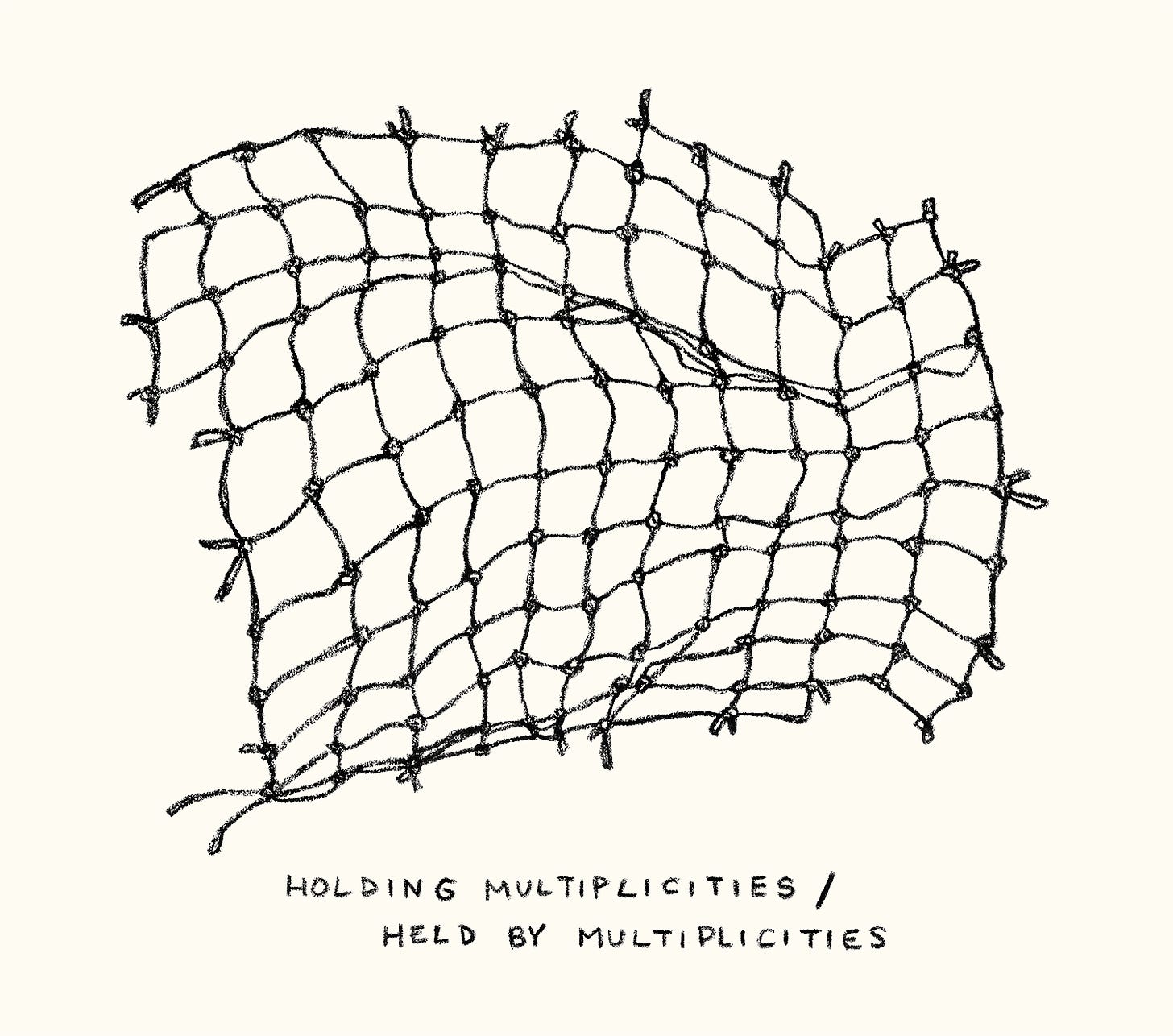

In the same way as the metaphor of Indra’s jewel net —a web with a jewel in each node, so each jewel is reflected in all of the other jewels— creativity is expressed in this context of interconnectedness and serves the world it is created in. We are multi-dimensional, as much as it is easier to just organise the world in simple labels, flat boxes, and in terms of usefulness. There is a net we are part of, that nurtures us — one we have to take care of.

Sources + Further reading

— [1] Byung-Chul Han and capitalism’s ‘death drive’, by J. W. Horton (Canadian Dimension)

— [2] Interview with Sophie Strand (Advaya)

— The death of the artist: How creators are struggling to survive in the age of billionaires and big tech by William Deresiewicz

— My creativity is magic, not a brand by Annika Hansteen-Izora (Annika is Dreaming)

— How we're killing creativity by Alice Cappelle

— This tweet by @jessf_white

Creative prompts

✸ Divide a piece of paper into different sections and write in each of them a different way in which you express your creativity (drawing, cooking, taking care of your plants, taking pictures of your pet…). See how every practice influences each other. Honour your multiplicity!

✸ Draw a web that reflects everything you are interconnected with. Think of it in terms of social relations, ecological relations, geographical relations…

✸ Journal about what connects you to art and creativity and see if what you currently do in your everyday life reflects that